It is justice that makes us human, not forgiveness.

This is a weird book.

In part, this is because it’s a contemporary adaptation of The Merchant of Venice, which is in and of itself a weird play. Along with Measure for Measure, All’s Well That Ends Well, and (sometimes) Troilus and Cressida, it’s been lumped in the category of “problem plays” for about a century. This is a category—now essentially discredited in academia, but still frequently used in popular discourse about Shakespeare—that critics invented for those of Shakespeare’s works that didn’t fit neatly into comedy, tragedy, English history, Roman history, or “romance”. (For more on Shakespearean romance, I direct you to my review of The Gap of Time, an adaptation of The Winter’s Tale.) The problem plays are deeply philosophical: they’re explicitly about ethics and morality, they’re not funny, and if there are any marriages at the end, the romantic or erotic lead-up to those marriages was certainly not the main point of the preceding five acts. When you watch one of Shakespeare’s comedies, you leave the theatre grinning broadly and feeling a little saucy; when you watch the tragedies, feeling drained and pared down. When you watch a problem play, you leave the theatre scratching your head and frowning thoughtfully.

A brief recap of The Merchant of Venice (which, incidentally, Jacobson does not provide): Bassanio is the titular merchant, who needs money that he doesn’t have to woo the noblewoman Portia. He asks a friend, Antonio, for a loan; Antonio doesn’t have hard cash, but he promises to be the guarantor if someone else will loan Bassanio the money. Shylock will; he’s a Jewish moneylender, and he hates Antonio, because Antonio is viciously, outspokenly anti-Semitic. He almost refuses the loan altogether, but eventually, he lays out the following terms: if Bassanio defaults, Shylock can take a pound of Antonio’s flesh as repayment. Unsurprisingly (see “the gun rule”: if a gun appears in act one, it must go off by act three), Bassanio does default–all his ships are lost in a storm at sea–and Shylock demands the flesh. Portia, Bassanio’s lady love, disguises herself as a lawyer and argues that Shylock’s contract gives him only flesh, but says nothing about blood, which he would have to spill in order to get what the contract allows him. Defeated, Shylock is dragged off to be forcibly converted to Christianity and to have his (considerable) estate divided up between Antonio and the Venetian government. Oh, and also, his daughter runs away with a Gentile.

There’s a little bit more to it than that, mostly involving some unconvincing and not particularly sexy or funny prancing about at Portia’s country estate, but that is the crux of the story.

I don’t actually feel competent to review Jacobson’s updating of the play, mostly because it (the novel) is all about Jewish identity, and I am not Jewish. The Duchess (who, long-time readers of this blog will recall, is my best friend from university and former housemate) is, and through her I’ve learned some things about what it’s like to live in a country that forcibly expelled your people in the year 1290, only to grudgingly re-admit them a few hundred years later; a country where large numbers of the mid-century social elite thought that Hitler, though a grubby little man, perhaps had the right idea; a country where casual, institutional anti-Semitism exists under the radar, so that no one believes you when you say you’ve encountered it. But I am not, and so I lose the nuance and weight of many of the conversations that pass between Jacobson’s two main characters–Shylock himself, transported to 21st-century England by some mystical means we are not meant to interrogate, and Simon Strulovitch, a billionaire art collector and benefactor who represents the Shylock character in the modern-day plot.

There are a few things that I can cavil at. One is the alarming nature of Strulovitch’s approach to fatherhood. His daughter, Beatrice, is sexually precocious and beautiful. He spends much of her adolescence driving around Cheshire and London, trying to find her, and dragging her away from parties by her hair (literally). He is bizarrely jealous of any boy she kisses. He is pruriently interested in whose bed she has been in, or will be in. This is waved off as overprotective Jewish fatherhood. Not knowing anything about Jewish fatherhood, I cannot speak to that, but to me it seems psychotic, abusive, and Freudian, and not something that you ought to be pinning on religious conscientiousness.

There is also the problem of everyone else’s attitudes to Beatrice. The crisis of the plot is precipitated by her apparent elopement with a footballer who is ten years her senior. She is sixteen, but evidence suggests that the footballer first slept with her when she was fifteen. She was essentially procured for him by Plury (the Portia character, a wealthy young-ish woman who throws a lot of parties) and D’Anton (the Antonio character, an also-wealthy gay aesthete and social butterfly), who are aware of the footballer’s proclivity for “Jewesses”, and find him one accordingly. It’s not just the gross dehumanisation suggested by the use of the word “Jewesses” (though Plury and D’Anton use it frequently); it’s also that, basically, they’ve pimped a teenager, and none of the resulting brouhaha treats that as a big deal. Strulovitch is more enraged that they pimped a teenager to a goy; Plury and D’Anton, when they realise that they could be in legal trouble, are so ridiculously naive in their shock that I wanted to throw things. Combined with Strulovitch’s original pervy possessiveness, and the many approving references to Philip Roth, it just all made me hideously uncomfortable.

Possibly, what we should take away from all of this is that it is much easier to update some of Shakespeare’s plays than others. Jeannette Winterson managed it with The Gap of Time in part because the original already had a slightly fairy tale aspect. I wonder whether the plot details of The Merchant of Venice meant that Jacobson bogged slightly; it certainly feels as though he’s much more interested in having Strulovitch and Shylock debate identity than in the movement of the plot, and those conversational sections were the ones I found most engaging. Shylock’s conversations with his dead wife, Leah, were also rather beautiful and moving. Perhaps if the whole novel had been a dialogue, it would have been more powerful; instead, more than half of it was irritating if not downright horrifying. (I suspect–with very little in the way of concrete evidence, I admit, but a lot in the way of gut feeling and experience with entitled old men–that Jacobson is one of those public intellectuals who would jump right on the “freeze peach” bandwagon with regards to misogyny.) So…buy it if you’re into Shakespeare, and buy it if you’re into the philosophical bits (I was both, and enjoyed it for that alone), but be prepared to either wade through the other half, or skip it altogether.

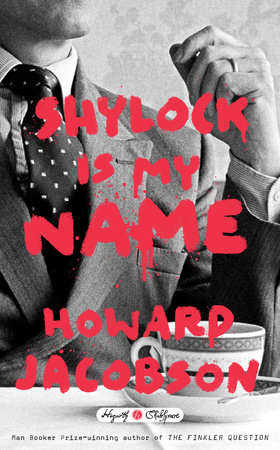

Many thanks (despite the above excoriations) to the kind folks at Hogarth for the review copy. Shylock Is My Name was published in the UK on 4 February.

I can’t comment on the book because I haven’t read it. However, I did hear Jacobson speak about the play last year and the very strong impassion I got was that when he was approached to be part of the Hogarth project the very last play he wanted to take on was ‘The Merchant of Venice’. I suppose this may have fed through into the writing.

But, I have spent the entire day wrestling with the play itself, which I think is far more complex than almost any other play in the canon, and I would include ‘Hamlet’ in that. Part of the problem is that we see it as Shylock’s play when it is called ‘The Merchant of Venice’ and should therefore be about Antonio. There are all sorts of reasons for this both to do with the writing and Shakespeare getting carried away discovering that he can create a character through prose rather than verse, and with the theatre history because the old actor managers used to play Shylock themselves and finish the play with his exit, thus loosing the last act completely. However, in the end I had a light bulb moment and decided that what we are really dealing with is the concept of the bond in all its personal, legal and religious meanings. Finally I think I can see my way through it. Which is a good job because I have to teach it next week!

Alex, yes, I think you’re spot on with the bond thing: what does it mean to keep our word to a person? What does it mean to *give* our word to a person? What does it mean to be loyal to our families/countries/gods? Very good stuff. Interesting that Jacobson really didn’t want The Merchant of Venice—if that’s true, it’s a shame they lumbered him with it. He obviously loves Shylock in the same way Shakespeare did, finding him (and Strulovitch) far more interesting than any of the others.

I heard the author talking about the book on public radio a couple weeks ago and it was really interesting. Unfortunately, at this point in time I can’t remember anything he said. All I am left with is a sense that he really wrestled with the play and the story, that he was really passionate about it, and that I was excited to read it after hearing him. Too bad it wasn’t quite what you were hoping for.

You can tell by reading it how invested Jacobson is; it’s just that some of the plots obviously didn’t interest him as much as some others, plus the aforementioned underage-sex/paternal possessiveness was undeniably weird…

This is an excellent review Elle. I adore Shakespeare but The Merchant of Venice is one I’m not particularly fond of.

I had a great time reading Christopher Moore’s retelling of the same play is his parody, The Serpant of Venice. This one sounds creepy like those dads who make their daughters wear t-shirts with the dad’s face on it when they go on dates.

The Serpent of Venice sounds really interesting, I must look it up. I wish Jacobson had just made this whole thing a philosophical dialogue, honestly. It would have been equally informative and less frustrating.

Hmm. I too like Winterson’s take on The Winter’s Tale; I was planning to read the whole Hogarth set but now I think I might skip this one. Thank you for the lively and informative review!

You’re welcome! It’s nice to have the “set”, I know. Maybe read the first few pages? It felt artificial to me, but I guess that’s sort of the point.

I’m sure it’ll turn up at the library soon, so I’ll take your advice. 🙂