By the time the tangy tomato sauce nips at the back of my tongue, I’ve already worked out the headline that will bring Freya down.

~~here be a few spoilers; I’ll warn you when they’re coming~~

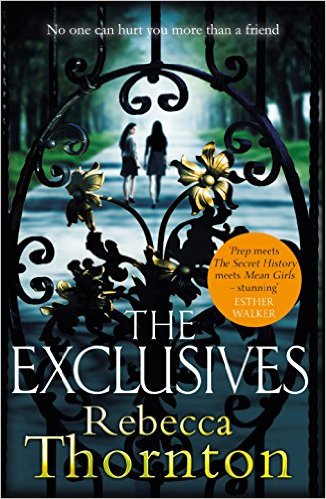

It’s a slightly weird experience, reading a book in uncorrected proof. There are usually a lot of forgotten quotation marks or left-out commas, which (you can be pretty sure, though not always) will be added in during the editing process; there’s often quite a lot of repetition, which you can think about likewise. Still, you don’t actually know what the book will look like, as a finished product. You can just hope. Most of the advance review copies I get are corrected and bound proofs, which means they’re essentially the finished book, which just happens to not be on sale yet. My copy of The Exclusives, though, is uncorrected, which means this review will be a sort of time capsule. I’m not reviewing the book as it is now; I’m reviewing it as it was in January. Take any criticisms, therefore, with the knowledge that the book may well have changed.

The “exclusives” of the title are Josephine Grey and Freya Seymour, two privileged girls at a prestigious (and fictional) English boarding school; the “exclusives” are also, by implication, boarding schools themselves, and the bizarre bubble that surrounds their inmates from reality. That bubble extends to the world outside of school: Josephine’s father works for the Prime Minister and gets her an interview with the PM for the school newspaper, while another character, late in the book, says that she’s sure her father will be able to ensure her place at Oxford. Unlikely as it seems that David Cameron would give an interview to a school newspaper, consider that my friend Ella, who went to an elite girls’ school in north London—not the same thing as Eton or Cheltenham Ladies’ College, but still—experienced regular talks by the likes of Imelda Staunton and Emma Thompson. This world exists.

The book doesn’t start in 1996, though—instead, we’re dropped into Josephine’s life in 2014, as she’s heading up an archaeological dig in Jordan. She’s successful in her profession, less so in her personal life: she’s maintaining a supposedly no-strings fling with a charming but irresponsible foreign correspondent. An email from Freya, however, throws everything out of balance: she’s found Josephine’s contact details, and she wants to talk about what happened eighteen years ago. We don’t yet know what that was—we won’t know for sure until the final twenty pages of the book—but whatever it was, Josephine absolutely does not want to revisit it. She’s forced back to England, though, by her mother’s illness: she’s thought to be dying, and Josephine is summoned to London to say her goodbyes, where she’ll have to face her past.

The novel is split-narrative, alternating its chapters between 1996 at Greenwood Hall and 2014 in London. Josephine narrates in both timelines, which at first seemed like a missed opportunity to integrate more perspectives, but which quickly came to seem like a very clever idea. It enables Josephine, and Thornton, to maintain complete control over what the reader knows, both about the past and about the present. The extent of that need for control tells us everything we need to know about Josephine: her strong will, her arrogance, her single-mindedness, her determination, her fear. The greatest terror of her life is that she will end up like her mother, a mentally ill housewife with no degree or accomplishments of her own, fighting off the voices in her head. The antidote to this fate, she is convinced, lies in winning a place at Oxford.

I have to say that, although linked scholarships were only abolished very recently, and may have been around as recently as 1996, I do not think that the Oxford admissions process has ever been conducted in quite the way Thornton describes it. When I applied, in the autumn of 2009, I did indeed have to sit an aptitude test (as all applicants for English literature, history, any foreign language, or biomedical science have to do) and attend an interview, but the idea that the interviewers might have gotten in touch with my school to say that my essay was “the best they have seen in years” is fanciful, at best. (Josephine is told by her headmistress that such was the opinion of the examining board.) Oxford tutorials depend on the ability of the tutors to manage and control the inevitable arrogance of their best students, which is not achieved by praising them before they’ve even matriculated. A tutor did once tell me about the excellent results of an applicant in the year below me (though she didn’t take up her offer, in the end), but I can’t imagine that she would ever have ensured that the applicant herself knew about that. And although we were never discouraged, we were also generally made to feel as though we could probably have done better, and perhaps would do so next week. It worked reasonably well as a corrective to callow youth.

Details aside, the major achievement of The Exclusives is the maintenance of suspense. Over nearly 300 pages, it’s hard to prevent your readers from guessing fully and completely what happened, but Thornton manages it, partly by providing two disasters. The first occurs on a night out in London; only Freya and Josephine experience it, and their differing responses to that trauma drive them apart when they return to school. The second disaster is precipitated, coldly and calculatingly, by Josephine alone, and is done as a sort of insurance plan against Freya telling anyone else about what happened. That catastrophe is discovered and has repercussions in 1996, but the first one, the one that really sets everything else in motion, remains unaddressed, and festers, until 2014. When Freya and Josephine eventually meet—and, of course, they do, despite Josephine’s attempts to stonewall her former friend—the events of that night have to come out. In the end, it’s Freya who remembers for them both. Josephine has spent her entire adult life suppressing it: she has airbrushed it out of her experience entirely, as an example of imperfection, of weakness and vulnerability.

Now for the spoiler-y bit: I wonder sometimes whether I want too much right-thinking, too much political correctness, in the books that I read, or whether it’s okay to want fictional models of situations that happen in real life being dealt with healthily and appropriately. Disaster # 1, for instance, the disaster that starts the ball rolling, is a relatively uncommon experience. You are much less likely to be raped and beaten by two strangers in a nightclub than you are to experience the same abuse at the hands of someone you love and trust. Disaster # 2, on the other hand, is far more common: an inappropriate relationship between a teacher and a student is something that, I guarantee you, has happened at every boarding school in the country during some point in its history, whether that relationship has eventually been made public or not. The teacher in question is fired, but there doesn’t seem to be any uncertainty about coercion; Freya is presented as having been totally in control of herself the whole time. Maybe we’re meant to see this assertion as a coping mechanism, or as necessary self-delusion; I don’t know. I just find it difficult to take at face value, and not a particularly constructive interpretation of the events that we’re given, especially in an era when decades-old stories of coerced minors are finally coming to light. Likewise, I don’t think that it’s particularly constructive to perpetuate the myth that rape is mostly something that strangers do to you when you’ve put some E in your drink. Novels don’t have a duty to be constructive, I know. I still struggle with this.

WE’RE DONE WITH THE SPOILERS NOW, YOU CAN TAKE YOUR FINGERS OUT OF YOUR EARS

The Exclusives is like a nasty Malory Towers, or a grown-up version of the Chalet School, with the terrible striving at its heart exposed. It’s dark and cruel and in some places melodramatic, but it sure as hell makes you want to know what happened. When Josephine achieves closure and catharsis at the end, it’s a relief; maybe we, too, can finally come to terms with the mean and selfish things we’ve done.

Thanks very much to Emily Burns at Bonnier for the review copy. The Exclusives was published in the UK on 7 April.