Hosted, as ever, by Bookish Beck. I had an absolutely immense library month in July! Bromley Central Library and the London Library both really came through for me, delivering many reservations all at once. And almost all of them were books published this year or last.

Several People Are Typing, by Calvin Kasulke (2021): The premise of Gerald, a corporate PR worker, having his consciousness accidentally absorbed into the Slack app—a conundrum which none of his coworkers at first notice, or, once noticed, believe, since staff sporadically work from home and it’s assumed Gerald is just “committing to the bit”—was irresistible. Written entirely in Slack messages, the novel reproduces with perfect satirical clarity the micro-environment of work group chats: the camaraderie and nonsensical inside jokes, the way managers write messages (and the way their presence in a group chat subtly changes the social dynamic), the subgroups and bizarrely specific use of emojis. The actual plot, which is sweet if slight, concerns one of Gerald’s coworkers Pradeep, who attempts to help Gerald return his consciousness to the physical plane (in the process, evicting Slackbot, which has escaped the app and taken up highly chaotic residence in Gerald’s body). There’s also some gloriously surreal content surrounding the dog food company for which the PR business is currently contracted to write social media posts, as well as Gerald’s experiences inside Slack (at one point, Slackbot turns him into a .gif of a sunset for 24 hours). There was scope here to tell a slightly darker story about corporate productivity culture that Kasulke doesn’t lean into enough, but it is the first book in absolutely ages to make me literally laugh out loud, more than once. At the very least, I guarantee it will get you obsessed with the :dusty-stick: emoji.

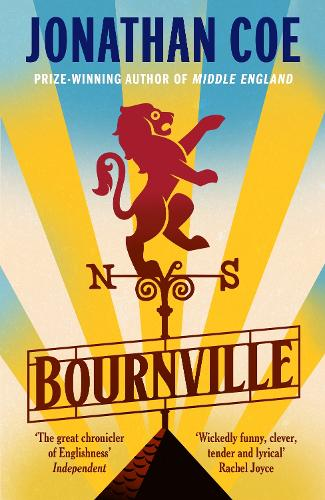

Bournville, by Jonathan Coe (2022): A state of the nation novel with heart and guts, a return to form for Coe, and the first Brexit/covid novel I have read that seems to actually answer the brief. I wrote much more about it here.

Standing Heavy, by GauZ’, transl. Frank Wynne (2022): First published in French in 2014 under the title Debout-Payé, which literally means something like “paid to stay standing”. I wrote more about this International Booker Prize-shortlisted novel that follows three Ivoirian men working as security guards in Paris here.

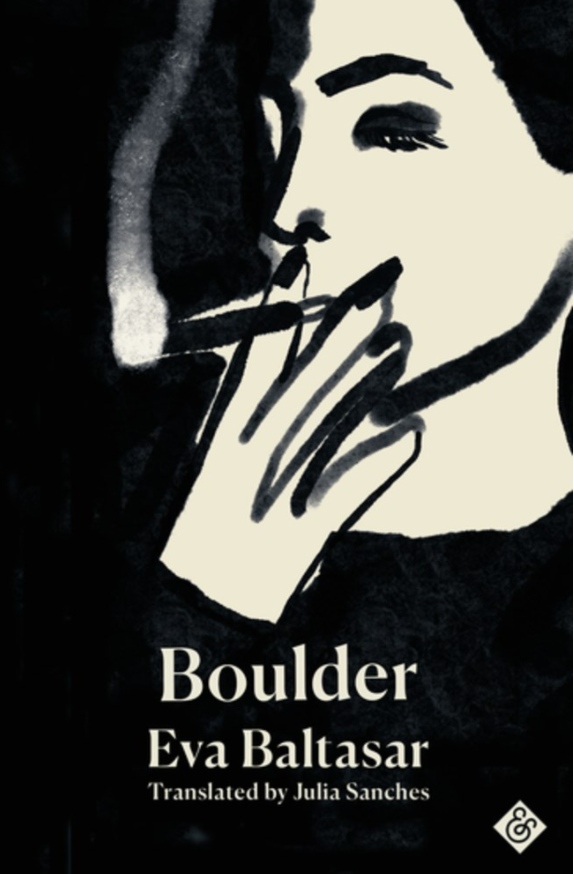

Boulder, by Eva Baltasar, transl. Julia Sanches (2022): First published in Spanish in 2020. I wrote more about this IBP-shortlisted novel that traces the fallout of a lesbian couple’s decision to have a baby in Reykjavik here.

Venomous Lumpsucker, by Ned Beauman (2023): My first Beauman, but it won’t be my last. A blend of goofiness, cynicism, hope, and dry humour set in a future where “extinction credits” provide a way for governments to get around environmental conservation regulations, Venomous Lumpsucker throws two characters together—amoral moneyman Mark Halyard and quietly despairing animal intelligence specialist Karin Resaint—to determine whether the titular fish still exists anywhere on earth. Mark needs to find out because, thanks to a global biobank hack of epic proportions, the price of extinction credits has just soared, and he’s about to get discovered in a nasty little fraud; Karin needs to find out because she was hired to do so, and also for secret reasons of her own. If the novel gets a little shaggy-dog in the middle, it does so with tremendous verve and style. I loved the section set in the refugee camp in Finland, where migrants from “the Hermit Kingdom”—Britain, now a North Korea-esque closed country out of which a very few agricultural workers are occasionally permitted to trickle—brew appalling analogues to tea and respond to almost any setback with a maniacally upbeat “mustn’t grumble” attitude. (One of them remarks on what lovely weather they’re having when it is in fact cloudy and grim outside, at which Karin loses her temper, only to be met with “Well, it’s not raining!”) An interesting read in conjunction with Bournville, and a great taster of Beauman’s wild imagination and assured authorial style. I’m tracking down the rest of his work in libraries now.

In Memoriam, by Alice Winn (2023): Another interesting read to compare to Bournville, as well as a read from last month, A Marvellous Light. Winn’s debut has already had lots of buzz: it follows two school friends, Sidney Ellwood and Henry Gaunt, from rugby matches and poetry recitations to the trenches of France, tracing the development of their romantic feelings for one another alongside the depredations of war on their extremely young psyches. I’ve read some less glowing reviews as well as some very positive ones, and understand the criticisms (mainly that In Memoriam shows us little that WWI literature hasn’t already covered in detail), but actually I think there’s something quite original about the way Winn weaves trauma with gentleness. These young men/boys have already been damaged, before they ever set foot on a battlefield—Ellwood and Gaunt are reminded by a younger soldier who comes from the same school that they once tied him to a chair and beat him all night, and they respond only with a kind of dismissive, jolly nostalgia—even those characters we’re given to understand are genuinely good people, characters we really are rooting for. Perhaps especially those characters. The combination of brutality and innocence that these teenagers have already absorbed from their society is a commonplace of WWI lit, sure, but I’ve never felt it conveyed so starkly, and also with such an acknowledgment of the limited, but real good things that could come out of that system: the comradeship between young men, the tenderness they show for each other when they’re wounded or depressed, the comfort of a shared repository of culture and memory. (Winn doesn’t shy away from class conflict, either; Hayes, an officer far more capable than the men who continue to be promoted above him, is a clerical worker from Lewisham whose accent and poor tailoring are conspicuously the reason for his failure to advance. His portrayal is sensitive, nuanced, and complicates the picture drawn of our posh young protagonists.) I enjoyed and was deeply moved by In Memoriam—Winn reanimates the past with great care and skill.

Wildfire at Midnight, by Mary Stewart (1956): On my birthday earlier this month, I took myself outside with a picnic blanket and a pile of books, and the one that won out—unsurprisingly—was Mary Stewart. I’m not sure there’s a better author to read on your birthday. The five (!) books I’ve read by her so far have all been good, though some better than others; the most recent one—also on my birthday, last year—was The Moon-Spinners, which was fine but felt like a dress rehearsal for This Rough Magic. Wildfire at Midnight, by contrast, is a return to form. Set on the Isle of Skye over a rainy Coronation weekend, it contains an excellently witty and sympathetic heroine in the form of Gianetta Brooke, a young model and divorcée; truly horrifying murders; a terrific suspenseful scene as Gianetta flees a killer in a blinding mist; and tremendous atmosphere in the form of a Scottish fishing hotel, complete with taciturn ghillies, kindly cook, and uniformly English guest list. Stewart at her best is capable of really expressing the moral evil of killing, and she does that again here: we understand the victims as not just bodies and plot points, but people who were truly loved and deserved to live. There’s also rather a good subtext about the arrogance and danger of colonising indigenous or pagan traditions. Wildfire at Midnight joins This Rough Magic, The Ivy Tree, and Thunder on the Right in the top tier of Stewart for me, so far.

What have you enjoyed from your library this month?