I haven’t made a habit of following the International Booker Prize particularly closely, but I’ve just read two of the books that made the shortlist and will read the ultimate winner soon. Here they are:

Standing Heavy, by GauZ’, transl. Frank Wynne (2022): First published in French in 2014 under the title Debout-Payé, which literally means something like “paid to stay standing”. GauZ’ is an Ivoirian writer whose own experiences in Paris have coloured this novel, which follows three immigrant men as they work a variety of poorly-paid security jobs. Ferdinand enters the country during the 1960s, when Ivoirian students are still encouraged and tolerated; Ossiri and Kassoum both make the move in the 1990s, “the Golden Age of immigration”, but the chilling effect of 9/11 on French immigration policy makes their lives more precarious. We spend time in the mind and memories of each man, as well as an unnamed retail security guard whose fragmented observations are by turns humorous, sarcastic, philosophical, erudite and world-weary. (A representative quotation that seems to encompass all of the above: “How is it possible to be reminded of the Laplace transform when watching an old woman with a purple rinse rummaging through a dumpbin of Gaby–WAS €24.95: NOW 70% OFF!–goose-shit-green striped cardigans?” And then there’s this: “At about one o’clock in the morning, the high-class escort girls and trans women who ply their trade on the Champs Elysees and surrounding areas drop by to freshen their fragrance and touch up their outlandish make-up. They share the aisles with women in hijabs, who, for reasons no-one knows, are numerous at this hour.” It’s that “for reasons no-one knows” that I like so much; that sense of phenomena that a person paid to become familiar with an environment can observe but not explain.) The three named characters could have withstood more expansive treatment, particularly Ferdinand, whose experience of political activism by means of students’-rights and anti-eviction demonstrations could have formed a rich longer novel on its own. The book is so short—252 pages long—that it can feel like there isn’t enough space to give each strand the attention it’s due; I would happily have read much more of the fragmented observations of the nameless Sephora guard, who clearly has a scientific background and whose character could have developed in interesting, subtly articulated ways.

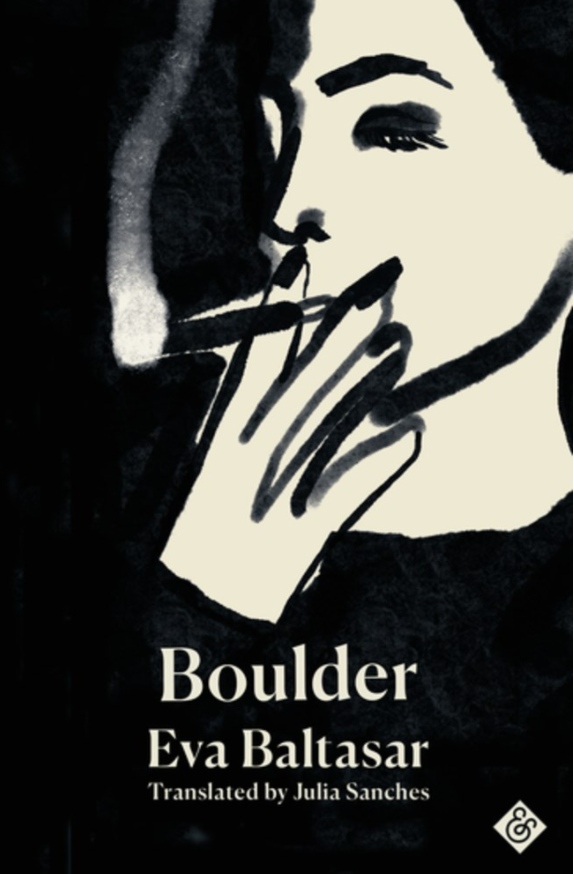

Boulder, by Eva Baltasar, transl. Julia Sanches (2022): Originally published in Spanish in 2020, though under the same title. Baltasar has said this is the second in a projected trilogy with the overarching name of “Triptych”, which is meant to explore the inner worlds of three different women. Eponymous Boulder starts off as a cook on a South American freighter (we never learn her real name) but soon falls desperately in love with an Icelandic woman named Samsa, for whom she gives up the sea and moves to Reykjavik. Their decade-long relationship is put under intolerable pressure when Samsa decides she wants to get pregnant and Boulder, uninterested in motherhood, feels unable to push back. It’s worth noting that although the birth and existence of baby Tinna has been presented in the critical discussion around this novel as the reason for the relationship’s failure, I don’t think that really gets to the heart of it. Boulder loves Tinna in her own way; she wants to spend more time with her than Samsa allows, and she wants to parent and be present for her in a way totally opposite to Samsa’s nurturing/smothering earth-mother-like constant attention. She is not maternal, but she is not uncaring. What sinks the relationship isn’t the baby; it’s Boulder’s and Samsa’s inability to connect up their individual capacities for care. Their communication, and the sense of them as a partnership, a team, is almost entirely absent from the novel. If this is Baltasar’s point, it’s a much more interesting and transgressive one than the exhaustingly prevalent babies-ruin-everything narrative; mainstream fiction has yet to plumb the depths of the emotional reality that babies are much more likely to ruin everything if there were cracks in the foundation to begin with.

Have you read either of these, or any other International Booker Prize candidates from this year?

I must admit to having lost touch with the Booker some years ago, mainly because I don’t read a lot of modern fiction. Boulder does sound interesting though.

The actual Booker is still one of those prizes that I feel ambivalent about, but the International Booker (for work in translation) has been throwing up some pretty interesting work in recent years, so I’m thinking of starting to keep an eye on it.

Definitely – I’m much more drawn to translated work nowadays than I am to mainstream fiction!!

The only one I read from the long- or shortlist was Still Born, which I found very worthwhile.

I read Still Born before the longlist came out and was pleased that it made it onto both the long and shortlists, although I think I’d have picked either Boulder or Standing Heavy over it. I’ve got a reservation on Time Shelter (the actual winner) and will read it next week, so I’ll report back!

Boulder is already on my TBR but Standing Heavy sounds really interesting as well.

Strongly recommend if you come across it! The anonymous guards observations in particular reminded me of my high school job in a bookshop; I used to jot down similar vignettes of weird customers and occurrences.

I just read Permafrost and then Boulder and enjoyed reading them together, Boulder is much more assured in the writing and the character. I found it interesting how the narrator so aptly describes her happiness being related to freedom, to being disconnected (to those she was at sea with), her structure and foundation pursued in the galley or the food truck, yet is unable to prevent herself walking into the very thing that will remove all that, realising too late the price she must pay for a desire that is going to wither and turn. The lack of knowing oneself, the inability to communicate in relationship, that loud and clear avoidance that signals whaties ahead.

It does sound like reading Permafrost together with this one would be an interesting exercise. Completely agree–Boulder can see disaster coming but can’t articulate it. In some ways (psychological verisimilitude, mostly), I think the novel might have benefited from some acknowledgement of Boulder’s and Samsa’s parents and early lives–where else does this rootlessness, or desperate desire for roots, spring from, after all?

Interestingly, after reading and kind of grappling with those very different characters, whose only connection really was through desire, I read that they are like mirror images of the same person – the author. In that sense they are easier for me to understand, as twin aspects of the same person, (uncomfortable corners of the self, dark, “often repressed and at times wholesale denied”) whereas the character of Boulder on her own was something of an enigma.