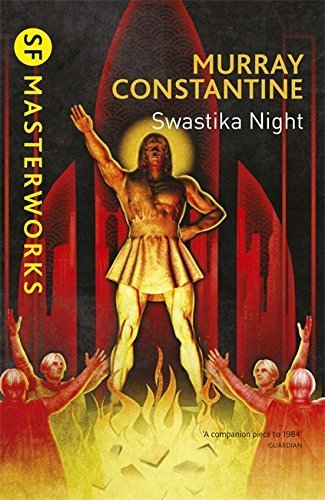

Written by Katharine Burdekin, but published under the male pseudonym Murray Constantine, Swastika Night has got to be one of the earliest “what if the Nazis won?” novels, given that it was published before Britain even entered the war. Constantine takes a long, and a dim, view: seven hundred years (!) later, the Nazi Empire rules half the world, while the Japanese have the rest. As one character explains, there are two ways to maintain an empire of this size: assimilate all your subject peoples (à la Rome), or stratify your society ruthlessly. The latter is the choice these Nazis have made: Germans are better than any other nationality, Knights (a hereditary priestly and administrative class) are better than any other Germans, Christians are tolerated only in their own ghettos, Jews (of course) don’t exist, and women–all women–are subhuman. Literacy is permitted only for men whose work absolutely requires it. Even then, there’s nothing to read except for technical manuals and the “Hitler Bible”. State religion is based on the worship of Adolf Hitler–always represented in statuary as a seven-foot muscular Aryan Übermensch–as God incarnate.

Into this established world comes Alfred Alfredson, an English man on pilgrimage to the holy sites of Germany. I like that Constantine is vague but evocative about what these actually are; we hear mention of Munich as the Holy City containing some relic known as the Sacred Aeroplane, and other sites known as the Holy Forest and Holy Mountain, but there’s no exploration of what events they memorialise, and that’s preferable. We can fill in the blanks from the names alone. Alfred is friends with a German Nazi agricultural labourer named Hermann, who previously spent time in England. Hermann beats a teenage German boy to death for attempting to rape a Christian girl (not because rape is a crime, although there are rules about attacking the underage, but because intercourse with a Christian should be repulsive for a German). This brings both men to the attention of the local Knight, von Hess, who immediately sees something trustworthy in Alfred (why? Unclear) and entrusts him with a great and terrible secret: an authentic photo of Hitler which gives the lie to his portrayal in German culture, and a handwritten book that memorialises the lost civilisation, history, and culture of the pre-Nazi world.

Swastika Night pre-dates Nineteen Eighty Four, but clearly influenced it. In particular , the many arguments between Alfred and von Hess seem to pre-figure the excerpts from Goldstein’s work and the conversations between Winston Smith and O’Brien in the latter. Similarly, both books suffer from an excess of argumentation, although Orwell’s book is technically better, and more famous, because it manages its philosophical content somewhat better. What Constantine is good at is imagining the deleterious, indeed self-destructive, traits of a fascist empire. The focus on violence and bloodshed, and the utter denigration of the female, is going to wreck the Nazi Empire within a few decades, von Hess guesses. There finally isn’t a war on anymore, which is one problem. And there aren’t enough boys being born, which is another. The women, somehow, subconsciously, are producing more and more girls.

It’s a really interesting, and horrifying, idea and premise. The biggest issue is that I don’t buy it. Not that I don’t buy gross misogyny and the fetishization of violence, but I don’t buy that every trace of pre-Nazi culture could be destroyed. I simply don’t. Von Hess claims it took about a hunded years and cost a fortune, but it was done; obviously this was an analogue world, not a digital one, but even so I don’t buy it. Alfred belongs to a resistance group (bafflingly only mentioned once); if such a thing, even toothless, exists after 700 years of Nazism, I simply don’t believe that organised underground preservation of cultural material wouldn’t have happened. From that, all else falls down too: men are indeed capable of hating and demeaning women to this extent, and internalised misogyny is also a thing, but Constantine seems to argue that the global population of women acquiesced pretty readily in their Reduction (it’s capitalised), and again, I don’t buy it. Not in the 1930s, not in the 2630s. Not all women, all at once, everywhere. It gives far too much weight to a desire to conform, not nearly enough to the possession of individual mind.

It’s still totally fascinating as a document from 1937, though–who else realised this early what the stakes might be? Apart from Eric Ambler in Epitaph for a Spy, perhaps.

Read for Kaggsy and Simon’s 1937 Club!

Wow, this sounds unexpected – especially for that year!

Right?! Who would have guessed.

I’ll be back to read this tonight. I was hoping someone would read it.

Yes!! Have you read this before?

No–I wanted to read some reviews. When I’m done at work I’ll read your review.

no

Fascinating! I’d heard of this and even contemplated getting a copy (though I don’t think I did). But despite its flaws it sounds so intriguing!

Don’t tell anyone but there’s a free scan available online as a PDF… it’s extremely interesting, I’d love to read more up to date crit of it.

Sounds interesting! I agree that it’s unlikely any regime would be able to destroy all traces of previous cultures, and I’m not even sure why they would. But I find the idea of conforming less hard to accept, especially women. We tend to forget that half the world still consists of societies where women collude in bringing up their daughters to accept a subordinate role in society. Generational brainwashing. I agree it would be hard for the more liberal societies to go back to that, but I’m not sure it would be impossible.

Of course, there are definite distinctions between cultures and women have internalised self-hatred in so many, for so many years. But I also can’t believe that the majority of women in every society would experience the thought process Constantine describes (“to make men happy, we must agree to being legally viewed as animals”) with barely any pushback or resistance. Even fictional situations like in The Handmaid’s Tale allow for the possibility, even the likelihood, of women in survival mode maintaining internal reserves of dignity and self-worth; Constantine suggests that the possibility of such internal reserves for women completely dissolved during the Reduction. It just strikes me as another way of viewing women as a monolithic population instead of a complex and diverse range of individuals.

Excellent review. Too terrifyingly real for me here in the USA. Maybe another time I’ll be able to read it. You did a great job.

Thanks! And, yep, fair enough.

Sounds fascinating. I do like a counterfactual narrative, and this seems ahead of its time in more than one respect!

It’s definitely worth a shot if you like this sort of thing. Keith Roberts’s Pavane is a more worked-out version of a not dissimilar idea (“what if the Spanish Armada won?”)

Reading between the lines – not difficult to do! – this sounds to be interesting as an exercise or premise but unsuccessful in its actualisation.

You don’t buy a lot of the details, and I’d start with the first scenario you draw attention to – that this is set seven centuries in the future: yes, Hitler envisioned his Third Reich lasting a thousand years but anybody with a smattering of the concept that nothing ever remains static would realise this is stretching the reader’s ability to suspend disbelief.

Still, even Wells in his 1933 future history The Shape of Things to Come got further and further adrift from history as it actually developed the further he got along his timeline!

Yes, I would say fascinating premise and not-uninteresting characterisation, but much of the detail doesn’t make sense for more than a minute. Obviously widespread illiteracy is also a pretty good built-in rationale for the failure of technology to advance, but I also don’t think that a fascist empire would choose to cripple itself to quite the extent they’ve done here (a global communications network that’s still at 1930s levels, for example).

How interesting that this was written so early on! It sounds a bit harrowing but I would agree with you that total erasure like that isn’t really possible. I’m not sure I’d even buy that all Jews could be eradicated like that. History shows us that no matter how many might try, there is always those who resist.

Plus the Great Reduction: even knowing what the state of global gender relations was like in the 1930s, I can’t convince myself that *all women on earth* would have subconsciously agreed that they needed to please men by acquiescencing in their own complete dehumanisation. It simply doesn’t ever shake out like that, not even in the most rigidly gender-separated societies.

I have a grandmother who would have been about 27 in 1937 and I find it nearly impossible to believe she would have ever done anything simply to please a man! And I don’t think she was that much of an outlier. There are subtle ways of course but such a total reduction flies in the face of what I see in the real world.